Murder! Killing in Art: Social, Political, and Cultural Perception of Otherness

Art lovers discretion advised.

Murder holds a controversial place in art history. From the depiction of martyrs to horror movies, the public’s fascination for violent art has always been criticised but seldom explored.

Yet, the dichotomy between the murderer and their victim allowed artists to explore the concept of otherness, and to question our position within it. Indeed, the way artists depict victim’s bodies encourages the beholder to think about their role in this vision. Are they mourners, or are they potentially projecting themselves as the killer?

When staging crime scenes, the artists were looking for more than theatrical effects meant to move or shock their public. Through their aesthetical choices, they revealed complex social, political, and cultural motivations, marked by the mindset of their times. As a result, the evolution of the treatment of the murdered body in art paints a vivid picture (pun intended) of the historical perception of the other, and of strength versus vulnerability. The shift from the devotion attached to the wounds of saint martyrs, then to the sense of moral superiority associated with vintage crime scene photographs of poor people, and finally to the craze for body horror in films, speaks volumes on human empathy and its manipulation.

A difference of treatment between male and female victims

Surprised? Not really, I suppose. The choice between a male and female figure in art has always been an important one, with its share of gender roles and moral concepts. The man most often preserves his individuality, while the woman is almost certainly erased in favour of an ethereal allegory — a country, a virtue, or an intellectual activity. Outside of religion, murdered male figures most often belongs to a political context. They are linked to the notion of heroism, with engaged artists visually rewriting assassinations to amplify the monstrosity of the enemy, and to make a witness out of the spectator.

French painter Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat remains the most famous example of murder in art. It depicts Jean-Paul Marat, a divisive figure of the French Revolution who was murdered by a political opponent, Charlotte Corday. Marat, suffering from a skin disease, received the fatal blow while in a bathtub which eased his condition. The power of this painting resides in the fact that the artist staged a stripped crime scene to appeal to the viewer’s empathy. David removed Marat’s dressing gown to intentionally expose the skin, which he cleaned from all traces of disease, improving pity. The minimalistic background emphasises a feeling of emptiness relating to this brutal death. Corday has been erased from the narrative; only her weapon and the letter, still held by her victim, testify of her action. Thanks to these eerily simple and effective choices, David makes the beholder a mourner, assisting to a wake.

The message had to be straightforward to inflict the most direct impact possible on the masses, because his painting belonged to a campaign to replace images of martyred saints with those of revolutionary figures. The representation of Marat’s body, between macabre and idealistic, was meant to encourage the abnegation of revolutionaries, followers of the new secular cult devoted to “la Patrie” (the homeland), in their fight against the other, an enemy made ominously invisible by the painter. It can be noted that the artwork’s contemporary reception contrasts with today’s fascination for the gore. In the eighteenth century, critics deemed it “difficult to look at it for very long, so terrible is its effect.”

While the physical horror witnessed on battlefields and historical crime scenes was glorified in art, the violence on female figures had long remained a taboo. The martyred saint women appeared very much alive, their stigmatized but victorious bodies serving the propaganda of the Church, particularly with the Counter-Reformation. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, on the other hand, women's corpses began to pile up in works of art. When artists wanted to create societal commentaries, their vision of otherness often presupposed that the murderer was a man and the victim, a woman. This dynamic testifies of social anxieties.

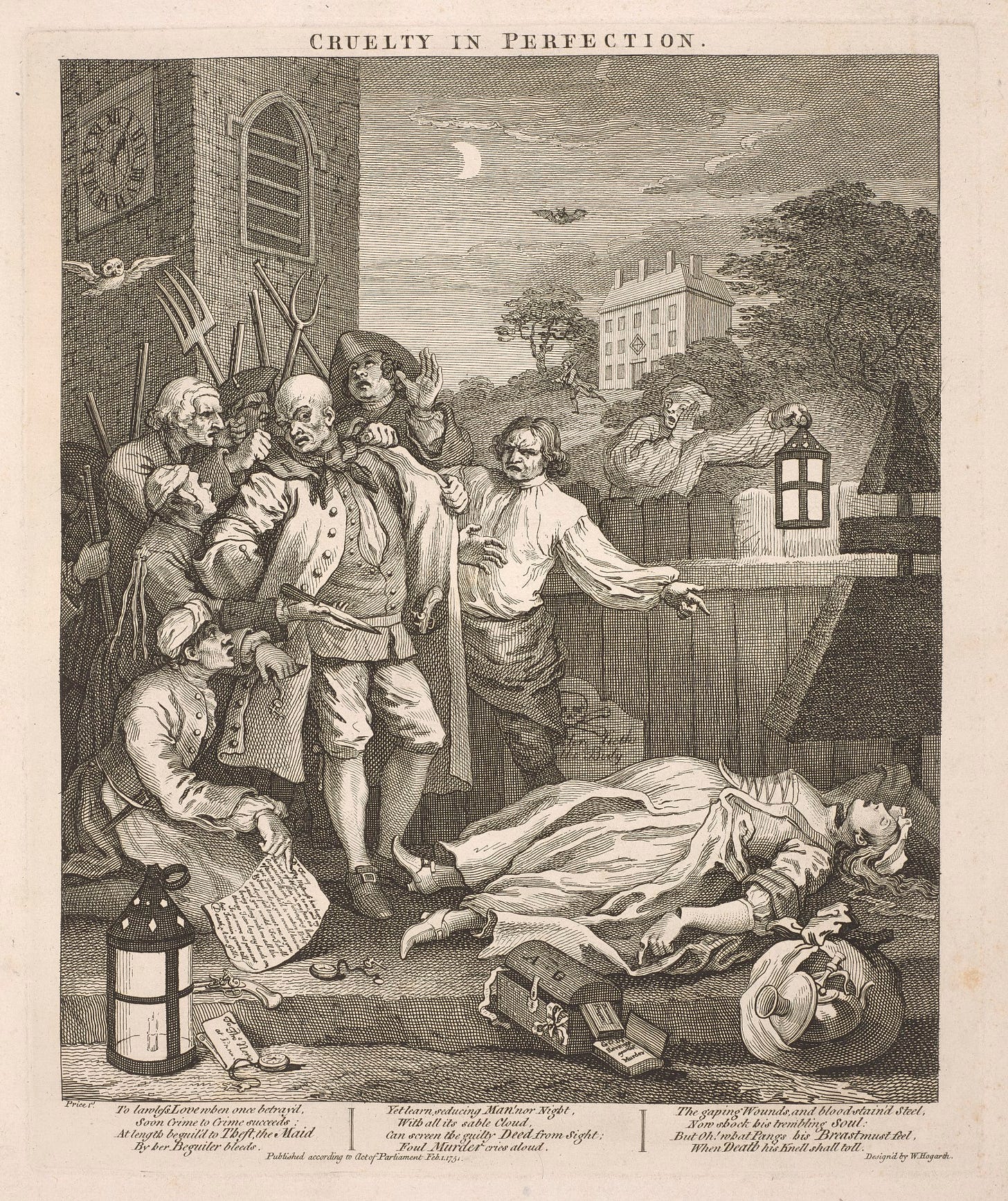

As in William Hogarth's The Four Stages of Cruelty, the depiction of a feminicide denotes concern for a very special other: the poor. The female corpse stands for the damage inflicted on society by the absence of morality resulting from wicked social conditions. Yet she remains anonymous; the male murderer, on the other hand, is a better-defined moral counter-example. A woman's body cries out: ‘don't be the murderer’, and then falls silent.

From moral caution to unabashed entertainment

However, even with the best will in the world, an artist cannot control the reception of his creation. The public's emotions are an often visceral and primal force, beyond all control, and humanity is hardly known for its natural goodness. Man is cruel. Our ancestors loved gladiatorial combat and public executions. It would be a mistake to believe that art lovers are more benevolent.

Czech painter Jakub Schikaneder had to face this sad realization when he saw the reviews of his painting, Murder in the House. The composition of his painting visually opposes the body of an unidentified woman, laying in a courtyard of Prague’s Ghetto, with a group of bystanders discussing her death with both passion and casualness. By choosing a canvas of large dimensions, reserved for noble subjects, the artist showed his interest in the poor’s fate.

The reception of his work at contemporary exhibitions nevertheless denotes a change of mindset towards otherness at the dawn of the twentieth century. Indeed, the public turned its back on the social commentary and preferred to perceive the scene as an early Whodunnit. The empathetic treatment of the victim’s body had transitioned to an incentive to voyeurism and sensationalism, which would later lead to the dehumanising craze for tabloid-like crimes.

In the twentieth century, journalism took over the lion's share of popular culture, and artists followed it, whether to denounce those who did not make the headlines or to indulge the fascination of the news. The divide between activism and mainstream culture widened.

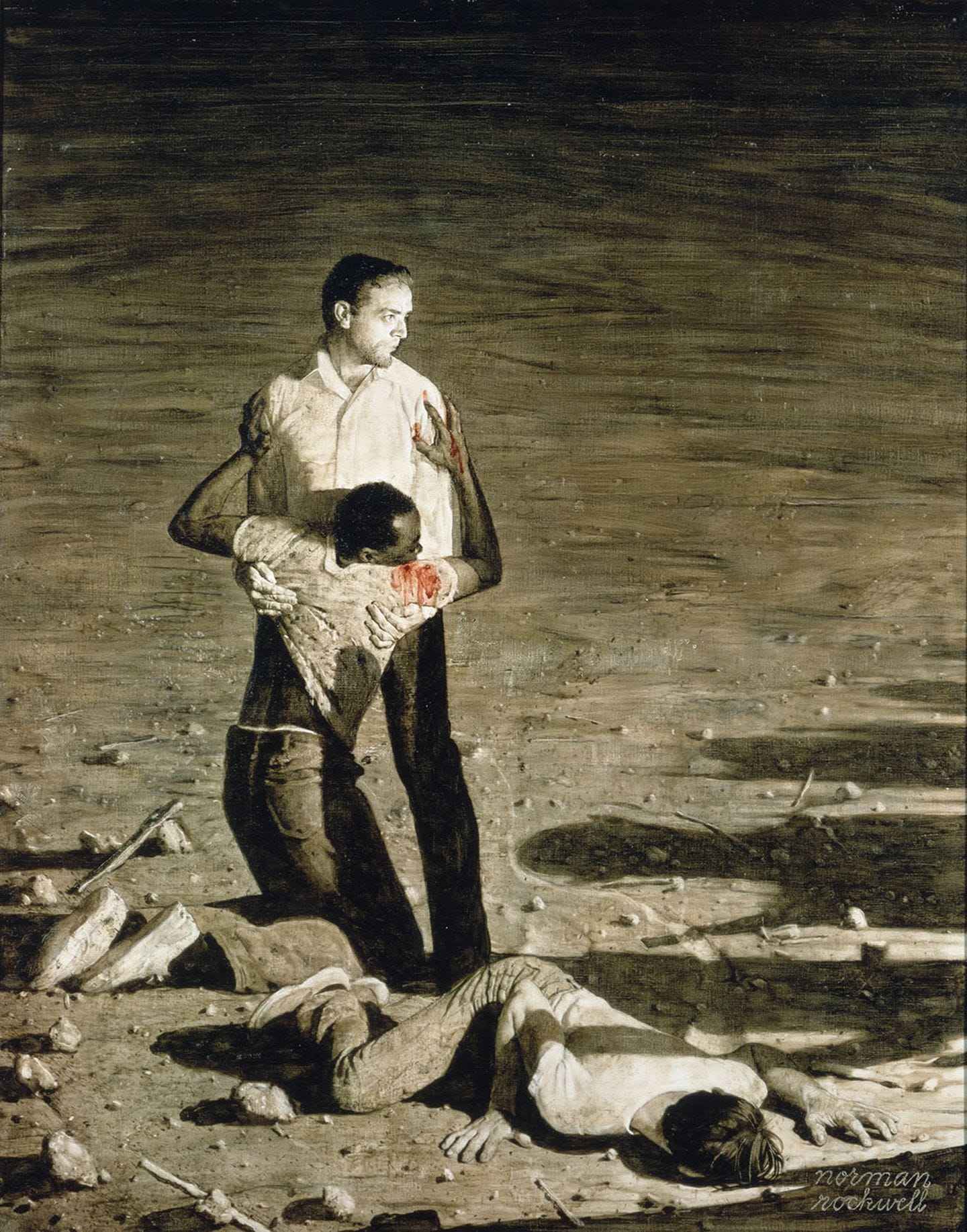

On one hand, works such as Norman Rockwell’s Murder in Mississippi challenge the audience to become more than a griever. Like David, the artist urges the beholder to action, here with a plea for civil rights and the fight against racism. Nonetheless, artistic crime scenes linked to social journalism have hardly taken their place in modern art, thanks to a far more radical medium, photography. In the pages of the newspapers, the ignominy of corpses begins to become commonplace. Crime scene photography brings a cold insight into the lives victims led, but also becomes an object of fascination.

Violence in figurative art is much more readily intertwined with opportunism, as artists very early on understood the chokehold of true crimes on the collective imagination. The heavy media coverage of human tragedies and monstrous acts, such as the crimes of Jack the Ripper and the Camden Town Murders, pushed some, such as Walter Sickert to profit from the popularity of sensationalist stories. They knew they would find buyers for their fictional insertions on real crime scenes that fascinated the crowds, and for which direct visual access was not permitted. The fate of the other becomes a source of enjoyment. The spectator as voyeur/potential accomplice, the artist as potential murderer. So much so that Sickert was recently suspected of being the most famous serial killer in history. And yet, he merely exemplified a change in mentality, and a new taste for gore. When he declared, “we like films and we like a good murder”, he was just heralding the cult of violence in cinema and TV series as we know it.

Eroticism versus catharsis

At the turn of the twentieth century, artists stopped aiming for empathy and started to indulge in morbid details. The emancipation of women was used as an excuse to justify the artistic mutilations of their flesh and their sexual objectification by the male viewers. This abandonment of decorum was activated in the West with the climate of world wars, but the fetishization of female corpses was already present in nineteenth-century erotic Japanese art, where BDSM sometimes bordered on the nightmarish, as in Yoshitoshi’s series Eimei nijûhasshûku (Twenty-eight famous murders with verses; impossible to reproduce here), a static precursor to exploitation films known for their misogyny.

German painter Otto Dix exemplifies the modern artists’ obsession with murder, as he created several paintings and prints inspired by it, sometimes using crime scene photographs as inspiration. This print depicts a woman mutilated in a fashion similar to Jack the Ripper’s victim, Mary Jane Kelly. Contrary to David’s dignified depiction of a male victim’s body, Dix’s female corpse is humiliated by the addition of copulating dogs. The artist’s grotesque treatment of the body could be explained by his experience as a soldier during World War I and his return to civil life, an expression of the contrast between battlefields’ male destruction and the female body, untouched by war injuries. For academics, twentieth-century murder artworks became the embodiment of the disruption of the modern social order in a stable bourgeois world. Dix, for his part, went as far as arguing that murder in art (especially toward women) acted as a prevention to real-life acts of violence on others.

The impact of barbaric fictional images on real-life crime remains a hot social and political topic. Public opinion has also yet to rule on the right of artists to integrate homicide into the cultural landscape, even if it fits perfectly the concepts of edginess, camp, or even comfort. Yes, comfort, as our passion for true crime stems from a thirst for justice, and the thrill of horror movie can provide a safe adventure outside of our contemporary lives that lack the danger our ancestors faced.

And yet, from 90s feminists protesting Bret Easton Ellis' novel American Psycho to recent walk-outs during the presentation of Coralie Fargeat's film The Substance at the Cannes Film Festival, our reactions to artistic killings are still as visceral as they were in the eighteenth century, even in a world where empathy is becoming deficient and the other more than often disregarded.

But why? Horror film fans often have more of an answer than art historians: we all end up using slaughter in art as a catharsis for our fear to end up being, not the mourner, not the killer, but precisely the victimised other.

Bibliography

Dowd, David L. “Art as National Propaganda in the French Revolution”, The Public Opinion Quarterly 15:3 (1951): 532-546.

National Prague Gallery. “Murder in the House”, https://sbirky.ngprague.cz/en/dielo/CZE:NG.O_5736

Tatar, Maria. Lustmord, Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Tickner, Lisa. “Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime”, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/lisa-tickner-walter-sickert-the-camden-town-murder-and-tabloid-crime-r1104355

Upstone, Robert. “Sensation: The Camden Town Murder”. In Modern Painters, The Camden Town Group, edited by Robert Upstone, 130-137. London: Tate Publishing, 2008.

Vaughan, William and Helen Weston, ed., David’s The Death of Marat. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

This is a really nuanced discussion of such a weighty topic! Thank you so much for sharing this.