You really asked WHY you are expected to be quiet in an art gallery?

Well, I have an answer.

This question was asked by a reader of The Guardian on Sunday 23 March 2025, for other readers to answer. As someone who has spent a considerable amount of time in art galleries, museums, and affiliates, both on my personal, academic, and professional time, I have, of course, had numerous occasions to ponder about it. This is my response (whether or not it gets published in the Guardian), inspired or not by real-life experiences.

Why are you expected to be quiet in an art gallery?

It is a recurring question in the art world, one asked by art students and gallery professionals alike. Why are you expected to be quiet in an art gallery (or a museum or heritage site for that matter)? That question usually leads to a passionate but always pragmatic debate.

When asked by a member of the public, on the other hand, it can be met with eye-rolling and a certain amount of annoyance. So why should I avoid having a hilarious conversation on the phone while visiting the National Gallery? Why can't my children sing Cocomelon songs in the middle of the Ashmolean Museum? And why can't I roar with laughter with my friends in a room at the Saatchi Gallery?

While the majority of professionals are rethinking the codes of access to art galleries to diversify their audience and attract younger visitors, more and more voices are being raised to attribute a certain snobbism, even a distasteful elitism, to this request of quietness. As an art historian from a working-class background, brought up by self-taught parents who saw galleries and museums as spaces for growth, this position has always intrigued me.

I have never heard of a cinema, a public library or a hospital being called snobbish, elitist places. Yet in these buildings, too, a few murmurs are tolerated, if not outright silence and restraint demanded. Why are you expected to be quiet in these places? For others. It is a given that cinema-goers want to enjoy the plot of their film without the surrounding noise. Studying or reading in a library is justified by a need to concentrate away from the hustle and bustle of the rest of the world. As for hospitals, they are a place of rest for people experiencing different levels of pain. These three places have a lot in common with art galleries, so why should we behave differently inside them?

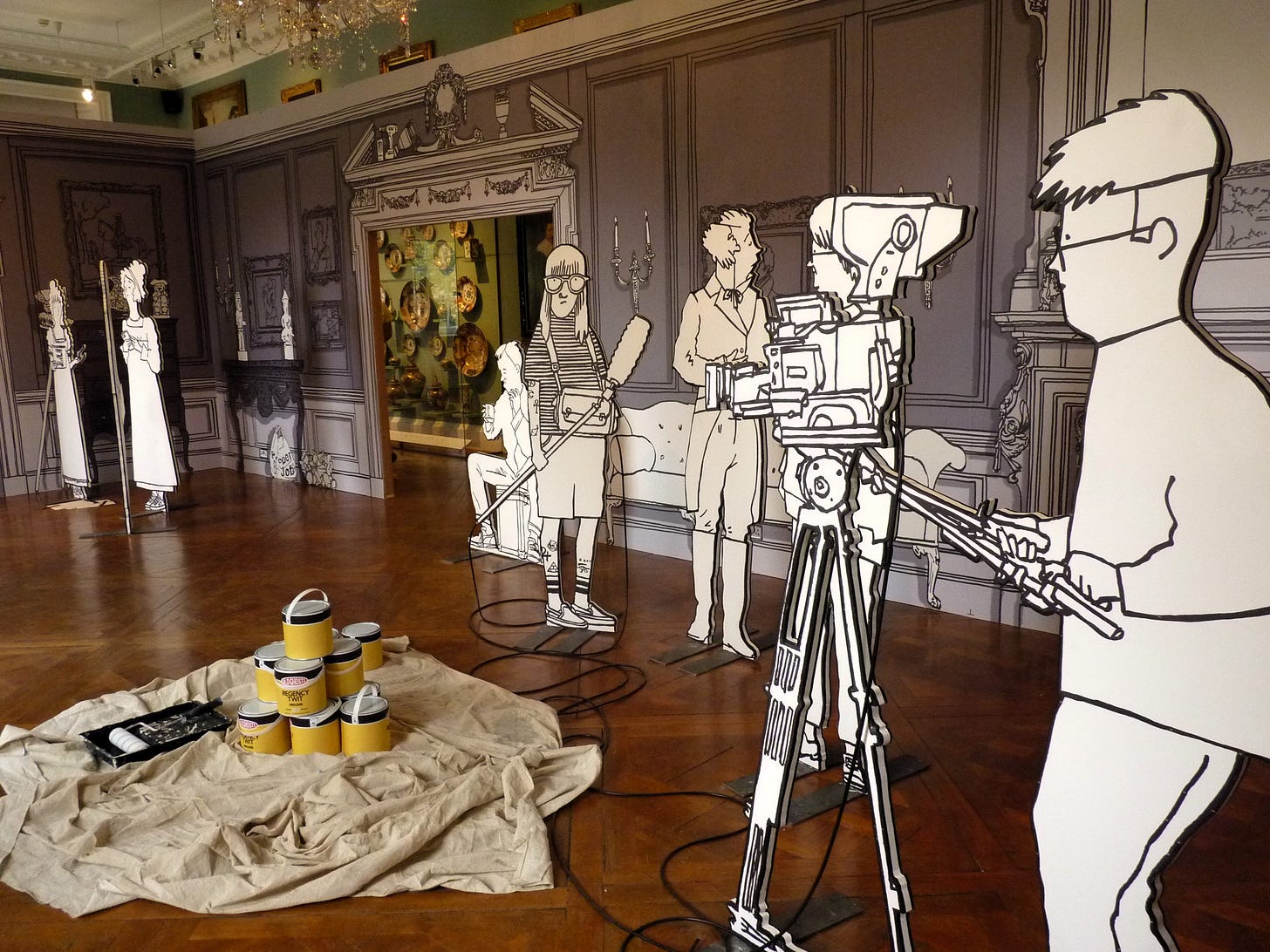

Some patrons watch an artwork or an artefact the way they would watch a movie, immersing themselves in the entertaining visual intrigue portrayed by the makers, using their imagination to watch them create before their very eyes, and feeling emotions linked to the aesthetic works in front of them. Your phone conversation distracts them from their immersion.

Other patrons came to learn, either on their own or as part of their studies. Ever tried to concentrate on a lesson with nursery rhymes singing in the background and children running around you? Whether it is to get an A or for personal development, a person who uses a gallery or museum for educational purposes has to be able to make the most of it. Finally, some people have different levels of tolerance to the noise, and they favour quiet places like art galleries to have some rest, to deal with or care for their mental health. These spaces have a reputation for being less hectic than the rest of the public realm, and so some see them as a haven of peace in which to manage their various levels of pain, whether physical or not.

In any public space, you are bound to a social contract with others, one that demands that you respect their space and their peace: this is what the quietness of an art space implies. No need to bring Locke, Rousseau, Hobbes, Socrates, or any other philosopher in the conversation (you can still go read about them if you wish to); it sounds like good sense to take others and their needs into account when you share a space with them, especially a space as peculiar as an art gallery and museum. Their administrators are free to organise special times for people who want to shout to break taboos. But the rest of the time, visitors are free not to have their ears broken.

Asking about the logic of quietness in these spaces without acknowledging the rest of the patrons denotes a certain selfishness that seems so fashionable in our modern society. For a moment, just a moment, you can dispense with being the main character in a film, entitled to your loud lines and your actions in the foreground, neglecting the extras in the background. Because in fact, you are just the annoying person in their reality.

Quiet is one of the things I like about art museums. Call me a snob, sure. But I enjoy being able to stand still before a Rembrandt, a medieval reliquary or a mark rothko and take the time to take it in without music playing out of someone's phone behind me.

This was a really interesting read - I work in a community role in heritage, and quiet is both a barrier and a facilitator. I’m often the one running engagement programmes which make a lot of noise, and I love it, but as you say that way of engaging is very much not the norm and is confined to my remit.

I see this as widening access, mitigating barriers to just get people over the threshold, but this is only the first step and sadly is where much of the effort stops. We need to democratise our cultural spaces and show up in a similarly respectful way to spaces which belong to the communities we try to “target” with audience development etc.

Reverence and the ability to lose yourself in thought are natural responses to art and we should seek to elicit them as often as we can. This means really working with others to get to the meaning and value, rather than imposing silence upon them without first opening up the avenues for critical thought, and preparing to be challenged!